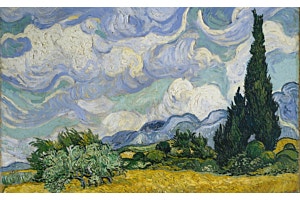

In honor of The Met’s stewardship of so many handcrafted treasures from around the world, our glass ornaments are hand-painted using a centuries-old technique originating in China toward the end of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).

Each artisan who produces our ornaments trains for at least a year, and spends between eight and 10 years honing the technique before they’re considered an accomplished painter. Only about six ornaments are produced each day by way of this careful four-step process. First, a design is mapped out on the inside of the glass orb using a fine brush. Next, it's colored in—dark pigments are painted first, followed by highlights to lend depth and dimension to the motif. Finally, a thicker brush is used to apply the background color, before the cap and ribbon are placed on the top of the ornament and the process is complete.

This season, we’re delighted to present a fresh fleet of hand-painted glass ornaments, each inspired by the Museum’s collection and crafted according to this historic technique. Below, sneak a peak at the creation of a Met Store ornament, and shop this season's latest introductions.

Birds of America Hand-Painted Glass Ornament Set

This charming trio pays tribute to three colorful commercial prints in The Met's famed Jefferson R. Burdick Collection of American ephemera. Two of the lithographs—Cardinal Grosbeak and Snow Bird—belong to a promotional series issued in 1888 by the Virginia-based tobacco company Allen & Ginter (American). Chickadee, from 1941, was included in New York author John H. Eggers's (American) eponymous Eggers Bird Booklets.

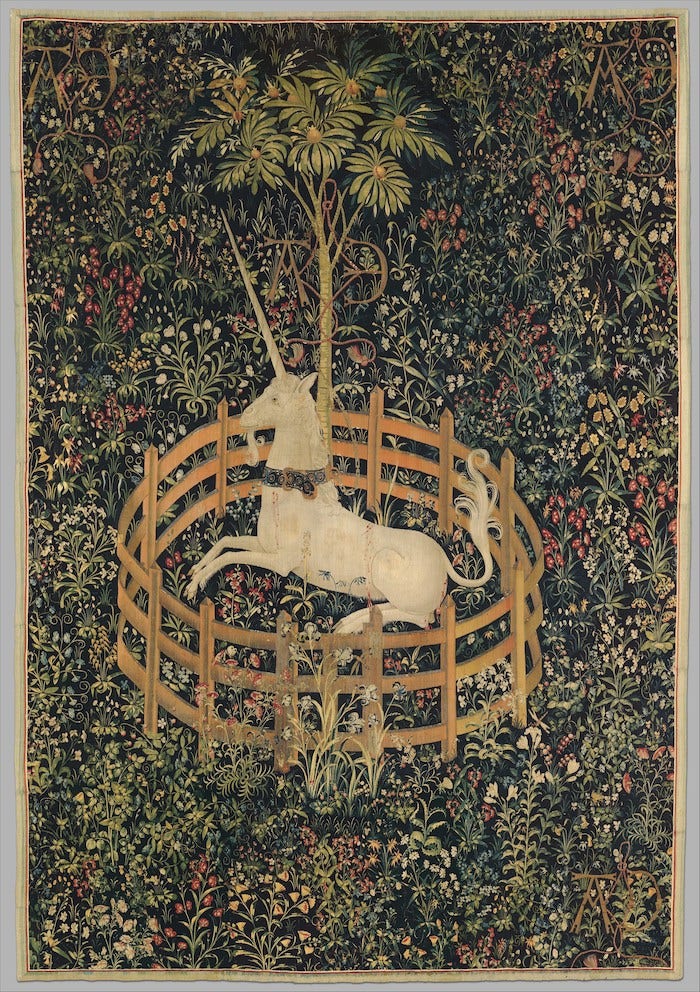

Unicorn in a Garden Hand-Painted Glass Ornament

The familiar image on this ornament references The Unicorn Rests in a Garden (1495–1505), an iconic French and South Netherlandish textile in the Museum's holdings. The medieval masterwork—a fan favorite at The Met Cloisters—depicts a unicorn resting in a garden enclosure beneath a pomegranate tree, enveloped by a millefleurs backdrop of richly symbolic plants. Though it may have been created as a single image, it's considered one of the seven so-called Unicorn Tapestries, which rank among the most visually striking and complex extant artworks from the late Middle Ages.

Dehn Spring in Central Park Hand-Painted Glass Ornament

Let the dreamy scene on our ornament whisk you away to a leisurely spring day in New York City. Adolf Dehn's Spring in Central Park (1941) depicts a verdant Sheep Meadow with midtown Manhattan landmarks—including the Hampshire House, Essex House, and the Empire State Building—rising in the distance. This bucolic watercolor, housed in The Met's Modern and Contemporary Art collection, is one of several seasonal vistas Dehn painted of Central Park and the New York skyline.

Tait-Henson Bower of Beauty Hand-Painted Glass Ornament

Bursting with colorful flora and lily-white doves, the festive tree on this golden glass ornament comes from Bower of Beauty (1966), a delightful painting by the celebrated artist duo Carl Tait and Lloyd Henson.

Tait-Henson Angel of the Evergreens Hand-Painted Glass Ornament

Tait and Henson are also behind Angel of the Evergreens (1964), the ethereal image celebrated on this hand-painted glass ornament.

Chelsea Botanicals Hand-Painted Glass Ornament Set

This lush trio reinterprets three porcelain plates in The Met's European Sculpture and Decorative Arts collection. Featuring lush illustrations of a flowering eggplant, a spray of lilies, and a tropical specimen, the Museum's plates were produced around 1755 by the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory. They're often referred to as "Hans Sloane" wares after the British Enlightenment-era botanist and royal physician. The exuberance and detail defining the original decorations reflect a growing public fascination with the natural world as global commerce brought exotic species from Asia, the Caribbean, and the Americas to England.

Shop our hand-painted glass ornaments online or in-store.