Concurrent with the 10th anniversary of the Museum's reimagined Islamic Wing—15 extraordinary galleries cohesively exhibited as Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia—The Met Store is delighted to introduce the Heirloom Project. This celebratory initiative commemorates The Met’s exceptional Islamic art collection and assists in the preservation of traditional craftsmanship by engaging with global artisans, such as studio potter-turned-entrepreneur, Anita Lal.

Lal established Good Earth in 1996 with a mission to revive the languishing practices of kumbhars, or village ceramicists, in her native India. Guided by a sensibility for sustainability and a discerning eye for design, Lal built Good Earth into a leading label that operates at the intersection of traditional artisanship and luxury retail. Visually striking and responsibly crafted, each piece encapsulates the bold beauty of the Indian subcontinent.

Here, Lal discusses her practice as a potter, the origins of Good Earth, and her partnership with the illustrious designer and Heirloom Project leader Madeline Weinrib to realize Blooming Poppies, a charming collection of tableware inspired by a magnificent late 17th-century Indian floorspread fragment in The Met collection, and now available in new pink and blue colorways.

The Blooming Poppies collection, designed by Madeline Weinrib in partnership with Good Earth

Tell us about yourself!

I studied psychology at Punjab University [and graduated] with a master’s degree, but after marriage I pursued studio pottery as a hobby while my kids were growing up. This led to an interest in traditional Indian pottery and a desire to add a new dimension to this age-old tradition by bringing it into the modern home.

What struck you about pottery as an art form?

As a studio potter, I was fascinated by the forms and textures of traditional baked earthen terracotta water pots, with perfect spherical forms that were beaten by hand. The artisanal tradition of creating utensils out of earthenware dates back over 5,000 years to the Indus Valley civilization. It is an unbroken tradition that persists today in almost the same form across the Indian subcontinent.

Blooming Poppies Serving Dish

What’s your philosophy as an artisan? Your process as a ceramicist?

To make water storage pots, the traditional process is to throw a heavy clay pot with a strong rim on the potter’s wheel. The pot is covered and left overnight until it becomes leather-hard. Using an anvil and a wooden beater, the pot is gently rotated and skillfully beaten until the walls become thin and a perfect spherical form is achieved. Then, it is dried and baked in a pit fired kiln.

Since the demand for earthen water pots was diminishing, I used the techniques of traditional potters to create large urns that could be used as planters in a contemporary home. To do that, I had to change the composition of the clay body to make the urns stronger and withstand higher temperatures for firing so that they became sturdy and impervious, unlike water pots, which need to be porous to allow evaporation and cool the water inside.

How does your ethos as an artisan factor into the identity of Good Earth?

The initial impulse to start Good Earth came from my desire to help rural potters create for contemporary homes using their inherited skills, which have been refined over millennia. Through Good Earth, I also wanted to celebrate the cultural heritage and design vocabulary of India, which is one of the most eclectic, diverse regions in the world, and where ancient artisanal traditions—ranging from handloom weaving and printing to handmade vessels in bronze and clay—continue to be practiced.

The design vocabulary of India has also inspired the world of textiles. Using indigos and natural dyes, Indian artisans of the Coromandel Coast created imaginative, fantastical, and colorful cotton chintz patterns, which have been prized and emulated the world over. The highly refined butahs (decorative motifs) of the Mughal era, along with an amazing variety of folk prints, have been an inspiration to designers across the globe.

Blooming Poppies Dinner Plate

What interests you most about the Heirloom Project?

The Heirloom Project celebrates the incredible artisanal heritage of Islamic culture by helping to keep traditional designs and craft techniques alive. It has been a pleasure to collaborate with Madeline [Weinrib] since we share similar values, and I am delighted to participate in this most relevant initiative to honor the heritage skills of diverse cultures.

Is there anything in particular that you hope the public will learn from or appreciate about this initiative?

Indeed, the most important aspect [of the Heirloom Project] is to sensitize the younger generation to the value of using and cherishing products made by the hands of men and women through skills inherited over the course of centuries. Living with well-designed, handmade products enhances our quality of life while sustaining livelihoods and traditions.

Blooming Poppies Oval Platter

Can you talk a little bit about your contribution to the Heirloom Project? What is it about the poppy motif that inspires you?

The Mughals had an amazing understanding of color and design, with a highly refined sensibility reflected in the arts, crafts, and architecture of that period. The pristine white marble Taj Mahal in Agra, with its exquisite artisanal carvings and pietra dura, or inlayed flowers, was the epitome of their desire for perfection and symmetry.

The poppy is probably the most iconic of all Mughal butahs. It is traditional and at the same time totally modern in its appeal. We recreated this beautiful butah based on a poppy-printed cotton cloth fragment at The Met. With Madeline’s direction, we interpreted it on products fit for contemporary American interiors. The artwork was hand-drawn and painted by our talented in-house artist and then converted into decals, which were applied to fine china dinnerware by skilled women artisans in our atelier on the outskirts of Delhi.

We also translated the poppy butah onto textiles by carving the pattern into wooden hand blocks, which were then used by master craftsmen to print on cotton placemats, napkins, coasters, and dramatic cushions.

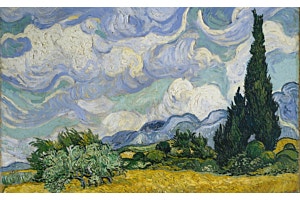

Fragment of a Floorspread, late 17th century. Islamic, Mughal period (1526–1858). Cotton; plain weave, mordant-painted and dyed, resist-dyed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Alice and Nasli Heeramaneck Collection, Gift of Alice Heeramaneck, 1982 1982.239a

Where else do you typically derive creative inspiration from?

Our creative inspiration begins with the diverse and ancient culture of the Indian subcontinent and extends across Asia, especially the lands that lie along the Silk Road. Their designs and crafts reflect an incredibly rich melding of eastern and western cultures.

Do you have a favorite Met destination?

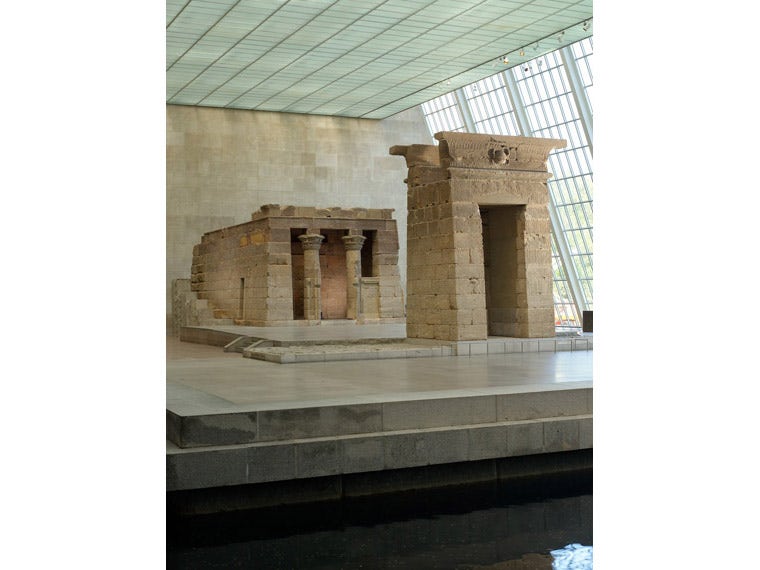

The Temple of Dendur is where I am transported—it remains the most memorable section of The Met for me.

The Temple of Dendur, completed by 10 B.C. Egyptian, Roman Period. Aeolian sandstone. Given to the United States by Egypt in 1965, awarded to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1967, and installed in The Sackler Wing in 1978 68.154

What's next for you?

All I want to do is to continue to learn. To absorb and translate aspects of various cultures and the heritage arts and crafts of our beautiful world.